I’ve always found this an awkward question to answer, not just because I am a Yorkshireman who’s lived more of his life down South than in God’s Own Country, but also because it touches on much of what caused me to end up as a lawyer living in London. For me, a lot of the awkwardness stems from the fact that where I am from represents something I’ve been trying to escape since I was 18, when I left home to go to university. It’s only relatively recently that I’ve come to accept that where I am from forms a large part of what makes me who I am, with the realisation that in my eagerness to escape, I turned my back on much of my past and in a sense forgot who I was.

I was born in Huddersfield in West Yorkshire, moving at the age of 6 months with my parents to Doncaster in South Yorkshire, where I lived until I was 18. I only mention my place of birth because it is sufficiently far north to establish my credentials as a northerner as well as a Yorkshireman, for those of you who consider that Doncaster’s proximity to Nottinghamshire makes me a midlander. That said, I’m not your typical Yorkshireman, or Doncastrian for that matter. I’m the only Yorkshireman in my family, I don’t have much of a Yorkshire accent, my other half is from Lancashire of all places, I don’t much like brass bands, I can’t stand Last of the Summer Wine and I’ll happily laugh at all the clichés involving flat caps, black pudding, tripe and whippets. But poke fun in a condescending fashion about where I grew up, especially if you’ve never been there, and you’ll see a very different side of my character.

Doncaster is a fairly unremarkable place, nestled in the industrial heartland of the UK about 20 miles from Sheffield. Although the local architecture took a heavy battering in the 1960s, its main misfortune was to be a town whose economy was based on coal mining and heavy industry in the 1980s when the economic reforms undertaken by Margaret Thatcher pretty much knocked the stuffing out of it, turning what was once an attractive market town into a fairly run-down and desolate place which felt more like a stepping stone to Sheffield and Leeds than a destination in itself. If asked to associate a colour with Doncaster at that time, I’d definitely choose dark grey.

Home was a village a couple of miles outside the town centre, what you’d call a “nice” part of town, sleepy and respectable. Apart from a rather saucy wife-swapping scandal involving the man who ran the post office, and speculation over the sleeping arrangements of two members of the WI who ran a health and beauty business from their house near the church, nothing much happened there.

Despite growing up in Doncaster, I never felt particularly connected to the place. All of my relatives lived in Edinburgh, London or Eastbourne, meaning that from a young age family visits involved travelling fairly long distances to places which from a child’s perspective felt very exciting; yes, even Eastbourne, where Granny and Grandpa Rimington lived, and which I visited every year during the Summer holidays, seemed vibrant compared with Doncaster. Significantly, it also meant that the other members of my family sounded very different from anyone in Doncaster, especially my aunts, uncles and cousins in London, who were terribly metropolitan and exciting. On top of this, my dad’s interest in Derbyshire (where he was born) meant that whenever we went on day trips, Yorkshire didn’t get a look in. As a result, I am the Yorkshireman who has never visited Ilkley Moor (with or without a hat), Harry Ramsden’s or the Yorkshire Dales. Years ago, when I was going through my anti-Yorkshire phase at university, I would have been proud to write that. Now I feel embarrassed and slightly ashamed.

I’m not sure what my biggest crime at school was. Overall, I think it was just being different. As a fairly shy and introverted boy who was a bit namby pamby and didn’t speak like everyone else, I stuck out like a sore thumb in a place where it really didn’t pay to be different. It also didn’t help being called Geoffrey, a name which sealed my fate as it caused me to be associated initially with a rather feeble character in a TV sitcom, as well as Geoffrey from Rainbow (although I think the association was indirectly with George, the pink hippo), and later on with a rather camp teacher at school. Funnily enough, no-one associated me with Geoffrey Boycott, the Yorkshire cricketer.

I first remember being made to feel different around the age of 8 or 9. At that age it was fairly anodyne stuff – the odd laugh at my expense based on perceived similarity to Larry Grayson or Frank Spencer, general “gay” sounds and mimicry as I was walking past, or “gay” actions involving limp wrists and Dick-Emery-style mincing. Nothing aggressive, just embarrassing and confusing. The fun and games really started when I moved to senior school at 12, where essentially I was a snooty poof as far as a lot of the older kids were concerned. If I wasn’t a snob, stuck-up or posh, I was a poof or a queer. One kid called me a “les” (ie a lesbian) because he didn’t consider that I was masculine enough to be referred to as a poof. As time moved on, the insults moved to the more anatomical end of the spectrum: arse bandit, bum boy etc. Faggot and batty boy hadn’t yet reached Doncaster. Of course, the younger kids learned by example and eagerly followed suit. It was pretty aggressive at times and, initially at least, quite frightening, but luckily it was never physical. The anodyne stuff continued in the background, becoming over time little more than a minor irritation, like a fly buzzing in my ear. Luckily there were enough decent kids who didn’t have a problem with me being different, so I tended to hang out with them. Also, I got on well with most of the girls, who clearly knew the score years before I did and cut me a lot of slack.

At that time I really didn’t know what I was. I didn’t fancy boys or girls and just needed a bit of space and time to work things out for myself. I wasn’t that nasty perverting influence from which the average homophobe thinks straight kids need to be shielded, and I didn’t deserve to be thrown to the lions to protect their children’s innocence. It never occurred to me to talk to my parents about it. Something told me that this was definitely not something they would want to hear about. This was provincial England in the 1970s and 1980s after all, a time when homosexuality was socially unacceptable to put it mildly and homophobia was tightly woven into the social fabric. Instead I retreated into myself and pretended it wasn’t happening. At this point I’d just like to emphasise that anyone who rolls out the old saying that sticks and stones may break their bones but names will never hurt them is talking total crap. Say something to a child often enough and sub-consciously they will start to believe it, even if consciously they reject it. That’s what happened to me. Not to put too fine a point on it, my experience at school messed me up for years. It also left me with a dread of sporting and social activities involving large groups of people, especially when I don’t know many of them. That friendly knockabout in the park with a football or departmental softball match might look like fun to you, but to me it brings back nasty memories of games lessons and the inevitable recriminations when I ended up on the team which lost the toss, not to mention my lack of sporting prowess.

Looking back, the bizarrest thing is that, initially at least, I didn’t even know what most of the insults actually meant and I don’t think many of the younger kids using them did either. They had heard older kids and adults using them, learning in the process that they were handy vehicles for expressing disgust, aggression and rejection. Whether or not I actually was gay was totally irrelevant; just being a bit effeminate and shy, and talking “posh”, was all it took.

For me Doncaster represented bigotry, intolerance and small-mindedness, and I couldn’t wait to get as far away as possible from the place. Perhaps not surprisingly I ended up at Sussex University. The amusing thing is that I had absolutely no idea about Brighton as a gay mecca at that point. For me, it was just a university town along the coast from Eastbourne, which was far enough away from Doncaster, but close enough to where my grandparents lived in case anything went wrong. It also happened to be one of the few universities that did the course I wanted to study. The first inkling I got that Brighton might be more interesting than I had initially thought was when the head of the sixth form at school summoned me to his office for a little chat to make sure I hadn’t made a mistake on my UCCA form, during which he made awkward and oblique references to Brighton’s Bohemian reputation. I told him I hadn’t made a mistake and wasn’t changing my mind, got the grades and kissed goodbye to Doncaster. After a couple of terms I was going to lectures wearing my dad’s dinner jacket, a black polo neck, 501s, and Doc Martens with steel toecaps. The head of the sixth form didn’t know the half of it. Neither did my dad, but his dinner jacket certainly saw an interesting slice of life.

After Brighton, I ended up in London where I have lived pretty much ever since (apart from a couple of interludes in Brussels and York). Doncaster was in my past, the place where my parents lived, to be visited only when absolutely necessary, preferably viewed from the window of a high speed train that didn’t stop there. I was the person who joked about being from Doncaster, buying acceptance by reinforcing every negative northern stereotype. To say I didn’t have a good word to say for the place would be an understatement.

Things started to change when my mum was diagnosed with cancer. I started going back a lot more often to see her and my dad, in the process spending more time with their friends, people I had previously only interacted with as a child. I started to talk to them as equals, gradually seeing a different side to them and Doncaster more generally. By that time I was also going out with my boyfriend Nick (aka the fella). Although I had finally come out to my parents a year or so before, I was still scared of taking a boyfriend home to meet them. I was still living that double life that anyone else reading this blog post who is L, G, B and/or T will know only too well, and was tired of sub-consciously editing everything I said to avoid revealing too much. I also wanted my mum to meet Nick before she died and I realised I couldn’t keep procrastinating. These days I can’t believe it took me so long to do it, but I suppose that just goes to show how much had been swept under the carpet over the years. Luckily it all went really well and Nick was an instant hit, not only with my parents, but also all of their friends. Looking back, introducing him to my parents was an important step in a process of readjustment which involved facing up to who I am and the realisation that, whether I like it or not, Doncaster is an important part of that.

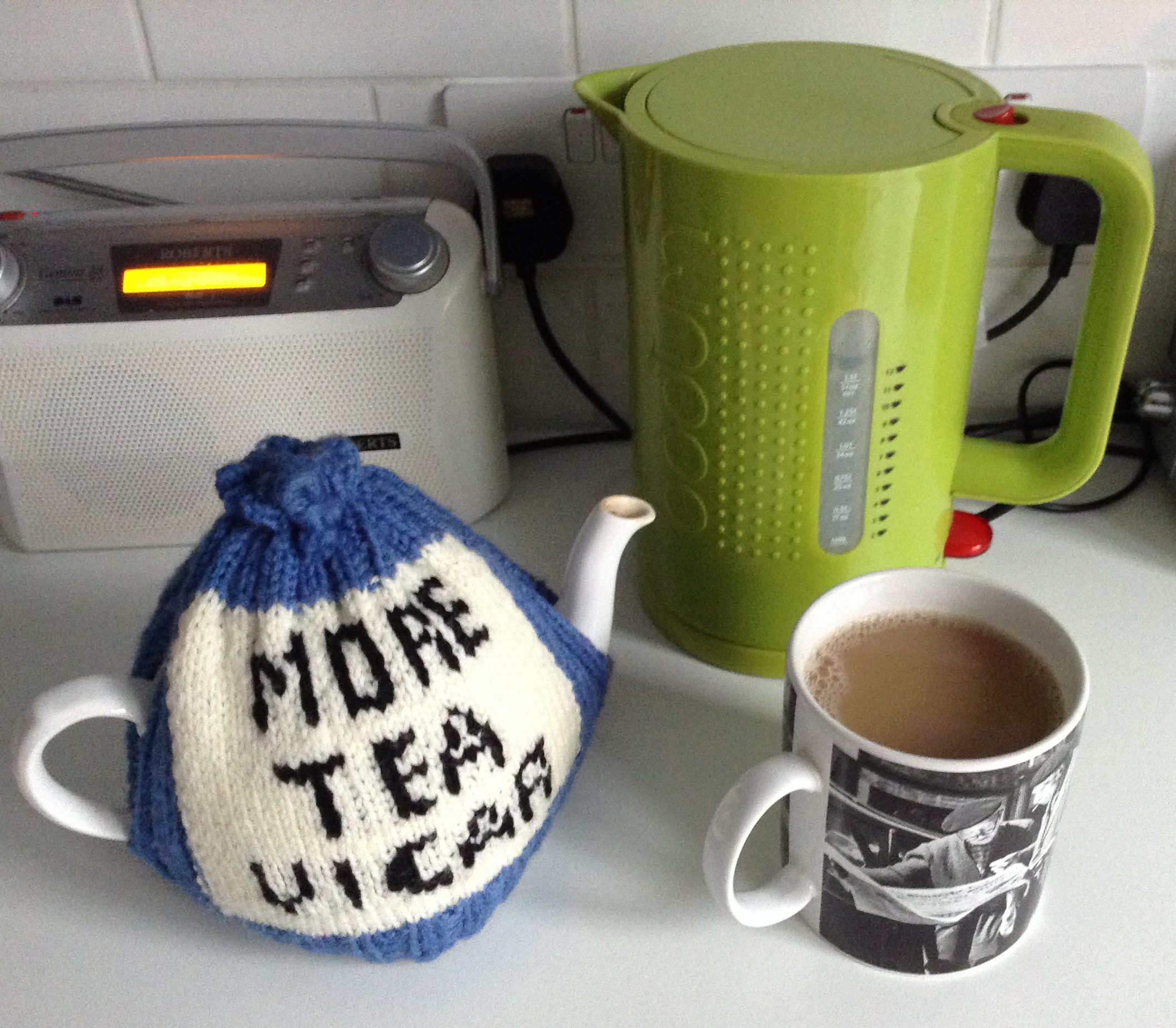

I can’t say that Doncaster will ever be my favourite place, but I’ve made my peace with it and these days I enjoy going back. I have a little routine which involves sausage rolls and pies from the village shop, a private moment by my mum’s grave in the local churchyard, a couple of pints in the village pub and/or in town at the local micro-brewery, and lunch at a place in the fish market which Jay Rayner reviewed favourably a year or so ago. If I’m feeling particularly adventurous, I might even have a glass of Prosecco with my fish and chips, raising a toast to the neighbour who once described it as “the latest thing in aperitifs” when serving it at a dinner party I went to. One of my favourite social events is a little tradition my dad has of going round to have “afternoon tea” with one of his mates. The basic idea is that we turn up, everything is set for tea, the wife “leaves us to it” while she goes out shopping, and then out comes the hard liquor for a messy afternoon of tea, cake and whisky.

If I go up to Doncaster without Nick, his absence is the first thing which is noticed, everyone asking when he’ll be going up next to visit. Sometimes I have to remind them that he’s from Lancashire to keep a lid on things. Most importantly, I know my mum was really happy to have met him before she died and my dad recently said that he sees him as a third son.

Over the last few years I’ve grown to see a lot of things differently. I’m not sure if that’s because I was blind to them due to other stuff going on in my life while growing up, or because I needed to leave in order to get the necessary perspective to see them in a different light, or because I needed to see them through older, more experienced eyes. On reflection, I suspect it’s a combination of all three.

The piece of the jigsaw puzzle I’m currently working on involves Yorkshire more generally. I’d like to see a lot more of the countryside, hopefully establishing more of a connection with the place in the process. Hence my forthcoming tour of every branch of Betty’s, which will involve elevenses and afternoon tea in Ilkley, Harrogate, Northallerton and York. Future projects involve popping north of the border to say hello to my connection with Scotland through my mum, and a trip to the northeast in search of the singing hinny, a relative of the Yorkshire fat rascal. But for now at least I’m focusing on tea and cake in God’s Own Country. What could possibly be better than that?